Oh my goodness!

Teaching about climate change isn’t easy when the last drops of hope for limiting warming to 1.5C evaporate with every US presidential decree. In response, I'm making a quantum leap in how I teach.

Stuck

“Think, think, think.” I’m feeling a lot like Winnie the Pooh these days, as I struggle to prepare for my weekly Environment and Society lectures and write academic papers about transformative change.

“Are you, by any chance, stuck? asked Owl.

"Oh no. Just resting and thinking, that’s all,” replied Pooh Bear.

“Yes, I’d say you were definitely in a tight spot,” said Owl, taking a closer look.

I do feel stuck. It’s hard to fully comprehend the short- and long-term consequences of the cruel and irresponsible “everything everywhere all at once” orders and decrees of the U.S. president and his administration and enablers. It’s even harder to teach undergraduate students about climate change and biodiversity loss amidst such chaos. Within the whirlwind of news, I’ve been resting, thinking, and stepping back to take a closer look at what I can do differently.

Predictable

Here we are in 2025, and the United States is removing references to climate change from government webpages. Canceling the U.S. National Nature Assessment. The implications of the latest decrees, which have been summarized by numerous journalists, represent a blatant assault on environmental and social justice.

This is by no means surprising. In fact, Project 2025 was intended to dismantle environmental protection in the United States and could sabotage progress on the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and other multilateral environmental agreements. It was predictable.

Within this context, I’ve been “think, think, thinking” about how to best teach students about climate change and biodiversity loss without adding to a sense of despondency.

Broken records

Low clouds of frustration, grief, and regret hang over me as I prepare for each class. I wish I could shake it off, but I also know I shouldn’t. Emotions like grief and anxiety are increasingly visible among both students and teachers in courses on climate change. It would actually be strange not to feel emotional about the current state of the world.

Climate change matters for many reasons. Some of those mentioned by students in our first meeting include uneven social impacts, human-nature codependency, the implications for food and farming, and justice. Emotions are surfacing, especially exasperation and fatigue. As one student pointed out, “we have been hearing about the importance of climate change all our lives, and still nothing is being done about it.” Julia Steinberger has written about this in an article titled ‘The kids are not okay’:

[I]naction is now perceived as a deliberate, inevitable choice. The grown-ups - and their grown-ups - know they are hurting and harming the youth and they are still doing it. The hurt and despair are immense. No wonder the high school students were muttering while I was pontificating to them about emissions and degrees of warming and impacts. None of that is seen to matter.

A friend who teaches a human dimensions of climate change course in Oregon sent me a message describing some of the emotions expressed by her students: “They feel that they were born too late to get to experience all the great things about this planet. They are angry about all the pep talks reminding them that they are the ones who have to fix the situation. They are tired of hearing about extreme records that are broken every year — and about how normal the weather used to be. They feel like they have ‘missed the boat.’”

Uh-oh. Maybe I’m the one who has missed the boat. Last week I talked about the science of climate change and all the broken records. I informed students about higher atmospheric concentrations of CO2 (426 ppm as of today), the latest rankings of the hottest years on record (2024 was highest in the 145-year record), and new examples of climate-related extreme events (too many to choose from this year). I probably sounded like a broken record.

Moving the needle

When I say broken record, I’m referring to damaged vinyl discs, where the needle gets stuck and the same words or sounds are repeated over and over again. When students hear the expression “broken record,” many think about how we are exceeding previous temperature and rainfall measurements, again and again. Both interpretations of a broken record require us to move the needle — that is, make noticeable progress towards a positive vision, such as a world where all life can thrive.

How do we do this? To move the needle, I believe we need to go beyond classical paradigms, policies, and practices. This means individually and collectively transcending dualisms like “us and other.” Right and wrong. Costs and benefits. Humans and nature. This isn’t easy in a polarized world, but it’s worth trying.

A quantum leap

Starting this week, I’m going to take a quantum leap and change the way that I teach my Environment and Society course. I won’t discuss quantum social change directly, but instead I’ll focus on possibilities for positive change (potentiality). I’ll emphasize that we as observers are always influencing outcomes (Copenhagen Interpretation), and that our beliefs matter (QBism). I’ll underscore the importance of a both/and perspective (superpositions), and highlight the significance of non-local, acausal relationships (entanglement).

To carry out my quantum experiment, I’ll draw on Paolo Freire’s pedagogical insights, including his emphasis on transformation rather than adaptation. In Pedagogy of Hope, he emphasizes that “[c]hanging language is part of the process of changing the world.” Changing our language means aligning words and actions and focusing on the results we want to see in the world. Shared visions.

I’m going to change my language and take goodness as a starting point in teaching. Goodness is the quality of being kind, fair, and beneficial to others. It’s also an expression of strong emotions, especially surprise. For the rest of the semester, I’ll counter the malice that is driving ecocide with an “Oh my goodness!” approach. This is not naive. In the spirit of superpositions, it’s important to both recognize and address what’s not working and amplify the fractals of change that are emerging all over the world.

Oh my goodness!

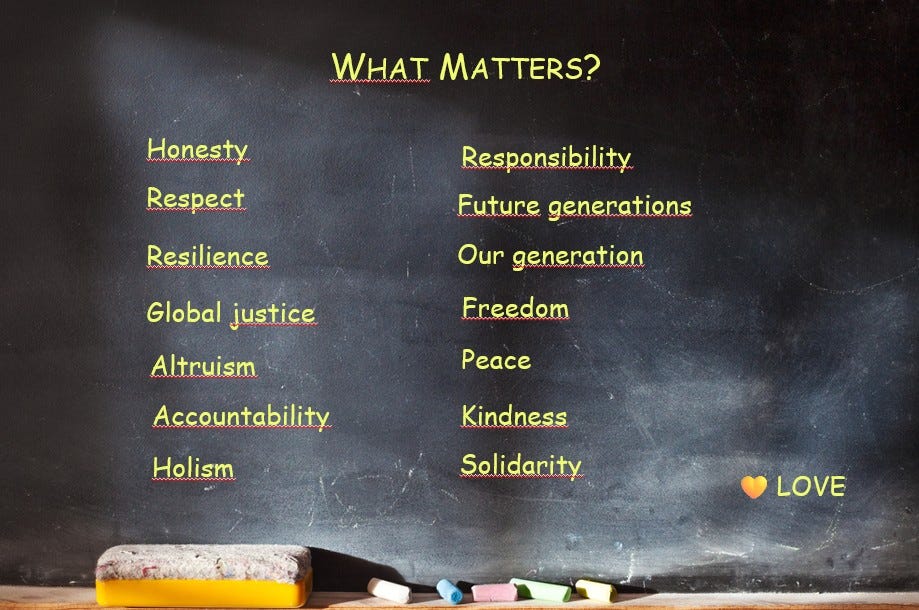

On the first day of class, I asked my students what they deeply care about, not only for themselves, but for all. They discussed this in small groups, then shared their values with the full class. Examples of universal values from this year (and last) include honesty, respect, altruism, and global justice. Goodness! These students care, and the class is a beautiful social fractal with transformative potential.

I want students to participate in the course knowing that they are among millions of others who care and are making differences that matter. I want them to feel a strong sense of individual and collective agency so that they can amplify goodness, which is critical in a time of callous and greed-driven politics. I hope they will understand that their actions, when grounded in what they deeply care about for everyone, can generate fractal patterns that make a difference.

Transformative change is possible.

An experiment

To generate transformative change within the current geopolitical context, transforming my teaching is a starting point. I’ll make quantum social change a resonant string that vibrates throughout the course. We will cover the curriculum plus more — but in a different way.

What if I were to apply this approach more broadly in my life, as an experiment to help us collectively get through these dangerous, fragmenting times? What if we all were to try it? Goodness, let’s do it! After all, as Hans Christian von Baeyer wrote in QBism: The Future of Quantum Physics, “unperformed experiments have no outcomes.”

You are invited to join this “oh my goodness!” experiment — and please share your results in the comments!

If success or failure of this planet and of human beings depended on how I am and what I do – how would I be? What would I do?

R. Buckminster Fuller

Your reflections and words remind me of some of the challenges I've faced in teaching about environmental stewardship to students in outdoor field environments. When I started, my approach was intellectual, orderly, and I thought rational. As failures taught me about what works and what does not work, both for students and myself, I learned that the more I work with the natural needs of students, rather than fighting them, the more we all felt good about the educational experiences and the results. Integrating social interaction and fun, with recognition of diverse personality and learning types, made a world of difference. Structuring lessons as competitions between groups made lessons exciting and engaging. Using metaphors and structuring lessons so the information was coming from the students rather than from any one source made things much less boring and much less stressful. Integrating ways to monitor respect and appropriate content inclusion was successful. People want to enjoy positive experiences and are willing to participate when given the opportunity. Evaluations to check cognition, integration, and attitudes about the material covered consistently showed these methods to be very effective. I stopped being drained and became consistently recharged by my work as an educator.

I wonder what would happen if all this information/practices/workshopping were available more broadly to people beyond college age? I have a real issue with telling these kids they are our only hope and they’re responsible for change when there’s plenty of older adults who crave this kind of learning/engagement outside of academia.