The Astronomical Fall

The autumnal equinox marks a turning point towards shorter, darker days in the Northern Hemisphere. In today's tense political climate, we may need to approach this astronomical fall differently.

Fall Equinox

Today is the autumnal equinox, when day and night are in balance before the shift towards shorter darker days, at least for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere. As the sun’s path crosses the celestial equator, it marks the start of our astronomical fall.

Reading the political news this week, it feels like we are entering into a different kind of fall. One that feels highly destabilizing.

To help myself get through the fall, I’m reading Bill McKibben’s new book, Here Comes the Sun: A Last Chance for the Climate and a Fresh Chance for Civilization. Despite today’s precarious political situation, he suggests that “we are also potentially on the edge of one of those rare and enormous transformations in human history.”

A Mission for the World

McKibben is talking about the potential and promise of solar and wind energy to reorganize the world in a more just and democratic manner. Recognizing that we are in a desperate race to cut greenhouse gas emissions, he sees the renewable revolution as far more than a technofix: “It could be a unifying mission for a divided world.”

McKibben is not sanguine about the challenges we face. Instead, he’s realistic and committed to helping people to understand the possibility of this moment. He acknowledges that “Big Oil will do almost anything to stay in the burning business, because their reserves of oil and gas are currently worth tens of trillions of dollars” but also points out that solar and wind power are much cheaper than energy from fossil fuels — and better for the planet.

I love Bill McKibben’s exuberance over the renewable energy revolution. Reading his book, I see that market logic may be the downfall of coal, oil, and gas, at least if we stop subsidizing them. But he also points to one of the biggest obstacles to the rapid adoption of solar and wind energy: people.

Local opposition is powerful and McKibben talks about the role of inertia and vested interests, including how misinformation and disinformation have been used to deceive people. He points out that “Change is always easier, cheaper, and less traumatic when it comes more slowly—that’s the most basic political reality.” Unfortunately, we don’t have time for this. Instead, we have to deliberately transform ourselves and our societies. Quickly.

Adaptive challenges

Rapid change involves adaptation, and this brings me back to a question that I’ve thought a lot about over the past decades: How do we adapt to changes that we are responsible for? Some years ago, I led a research project about the Potential of and Limits to Adaptation in Norway (PLAN). At the end of the project, we published an edited book called The Adaptive Challenge of Climate Change.

Adaptation, we contend, has to be redefined to include not only adapting to observed and near-term impacts of climate change but also adapting to the idea that humans are capable of transforming systems at a global scale.

In the book, we drew on the difference between technical problems and adaptive challenges, as distinguished by Ron Heifetz and his colleagues in The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World.

Technical problems are those that can be diagnosed and solved by applying established know-how and expertise. They usually call for improved skills, better procedures or management, increased allocation of resources to a problem, more innovation, or new types of governance. Even though technical problems are often complicated and difficult to address, it’s possible to identify, develop, and apply the required skills. It’s not a lack of options that blocks solutions to technical problems but rather issues such as costs and political priorities.

This technical framing sounds an awful lot like the current approach to the renewable energy revolution. It’s an approach to renewable energy transitions that’s been successful in some cases and contexts, and these are worth celebrating. For example, in Uruguay, it took only five years to decarbonize the grid, and at the same time created 50,000 new jobs. Yet, activating a solar revolution in the United States and many other oil-producing nations represents more than a technical problem — it’s also an adaptive challenge.

Adaptive challenges call for new ways of perceiving systems, relationships, and interactions, and they often require changes in mindsets, priorities, habits, and loyalties. The solutions to adaptive challenges don’t follow clear, linear pathways. Heifetz and his colleagues emphasize that “adaptive challenges are typically grounded in the complexity of values, beliefs, and loyalties rather than technical complexity and stir up intense emotions rather than dispassionate analysis.”

Shifting mindsets

In The Adaptive Challenge of Climate Change, we emphasize that successful adaptation fundamentally confronts our relationships to both individual and collective change, as well as our relationships to each other, to nature and to the future:

Confronting the adaptive challenge of climate change involves acknowledging that the problem is both systemically conditioned and socially constructed, which calls for new ways of engaging with the interlinked political and personal dimensions of climate change. This is quite different from technical and managerial approaches that tend to normalize the drivers and impacts of climate change or make them appear inevitable, then promote adaptation through better technology, more knowledge, or improved know-how, skills, and management practices.

Addressing the adaptive challenge of climate change, we wrote, “often involves engaging in difficult discussions, dialogues, or self-reflection that can potentially surface beliefs that are limiting, ‘facts’ that are taken for granted, assumptions about others, and ideas about what is possible or impossible.”

In other words, many systemic changes require more than structural or operational redesign: they require transformations in mindsets and ways of being.

Managing disequilibrium

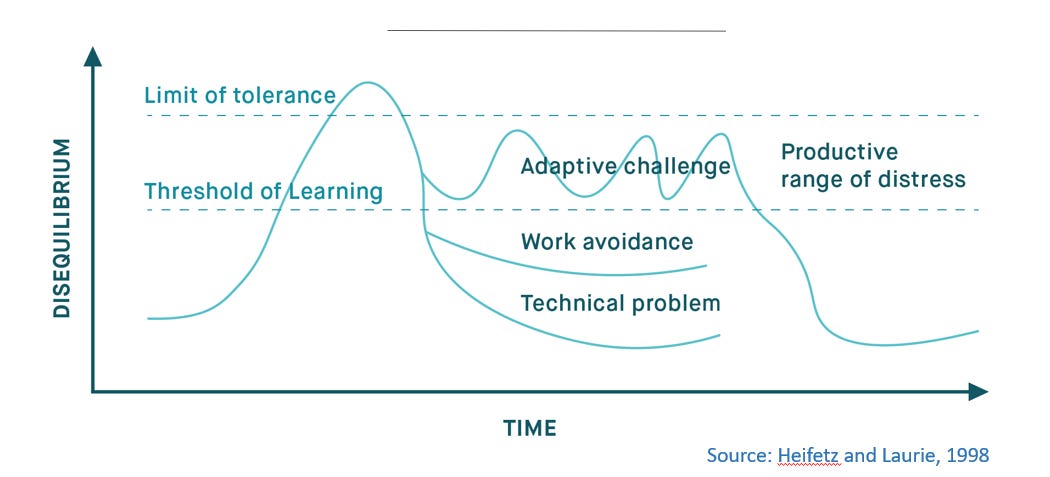

In The Practice of Adaptive Leadership, Heifetz and his colleagues include a figure that I’ve found helpful in approaching adaptive challenges. The figure depicts how adaptive challenges relate to our sense of disequilibrium over time. As disequilibrium grows, we reach a threshold of learning — a productive range of distress where we can handle adaptive challenges. If the disequilibrium is too high, we may go beyond our limits of tolerance, where there’s a tendency to either treat the challenge as a technical problem, or avoid it altogether.

Our productive range of distress is not static — it shrinks and lowers when we are struggling with health problems, economic uncertainties, violence and conflicts, relationship issues, loss of family and friends that we care about, or concerns about climate change and biodiversity loss. Or when we have too many worries to handle at once.

When the disequilibrium and distress is high, we need to support and help each other with courage and compassion. We need conversations, communities, and practices that help us engage with adaptive challenges, and notice when we are avoiding them or approaching them in a technical way.

Change is underway

Transformative change for a just and sustainable world is urgent, and fortunately a mindset shift is well underway. For example, ecocentric views are spreading and have the potential to create a profound shift in our ways of being in and relating to the world. Such views recognize human-nature interdependence, and acknowledge the limits of technical responses.

Paul Hawken describes this beautifully in Carbon: The Book of Life: “Replacing fossil fuels with renewables is crucial but insufficient.” He calls for a mindset shift that puts life at the center of all of our solutions.

The climate movement is alive and growing, but it cannot succeed unless we see the planet as a living entity, one and the same as earthworms, lichen, and lemurs. Life must be at the center of all we do or we will not live here much longer.

Hawken asks whether compassionate, effective, and brilliant communities of action can emerge from the chaos that we are experiencing now, emphasizing that “The word community is essential to solving the crises we face.” I could not agree more!

The Revolution

Our planet revolves around the sun, and as Bill McKibben argues, so does the future of humanity. In objective terms, humanity has about a billion years left on Earth before changes in solar activity render our planet uninhabitable. But the way we are currently treating the planet and each other, we risk cutting that back by orders of magnitude. As inhabitants of planet Earth, we all have a role to play in the revolution.

The word revolution refers to going around and around, like a wheel or the hands of a clock. It can be a cyclical experience that brings us right back to where we started. Revolution can also mean a change in a political, socioeconomic, or technical situation. As in the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, or the quantum revolution. However, the type of revolution we need right now involves shifts in ways of thinking about or visualizing something. It’s about embracing a new paradigm.

With darker days ahead, I’m reminded that fall in the Northern Hemisphere is spring in the South. The challenge is to hold both perspectives and focus on the light. After all, we’re in the midst of a solar revolution — a fresh chance for civilization.

The garden is growing dark

The stars are shining.

Let us, then, bow our heads to the earth's rhythms

And acknowledge the wisdom of change.

— Rainer Maria Rilke