The Entanglement of Species

Despite all we know, many species still face a growing threat of extinction. Do we need to pay more attention to concepts like entanglement and start acting like all species matter, including our own?

Biodiversity Loss

I’m in Windhoek, Namibia this week for the IPBES-11 plenary, where we are presenting the transformative change assessment to 150 member states for approval. The assessment is the result of the dedicated effort of 101 experts from 42 countries who have worked for over three years to assess what we know about “the underlying causes of biodiversity loss and the determinants of transformative change and options to achieve the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity.” That’s the full title of the assessment. Seriously!

Over the past weeks, I haven’t had much time to think about anything other than the assessment, let alone write a newsletter. But every now and then, I’ve found a moment to reflect on the many entanglements that got me here. It started decades ago. . .

Time travel

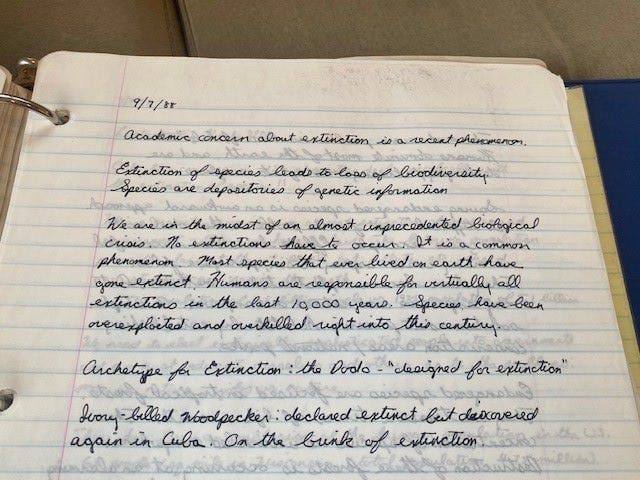

“We are in the midst of an almost unprecedented biological crisis. No extinctions have to occur.” These notes, dated September 7, 1988, were written on my first day of graduate school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I was taking a new course called “Extinction of Species.” Back then it was one of the first of its kind in the world. “Academic concern about extinction is a recent phenomenon,” the professor explained at the start of the class.

It was a life-changing course for me, opening my eyes to a world that I had not seen before. With no science background, UW’s environmental studies masters program enabled me to take courses like climatology, ecology, systems modelling, tropical conservation, paleoclimatology — and human geography. I listened, read, and took copious notes. The more I learned, the more I became aware of how unaware I had been. This inspired me to do PhD research on the relationship between tropical deforestation and climate change in the Selva Lacandona of Chiapas, Mexico. That’s another story.

The implications of biodiversity loss and climate change are overwhelmingly clear, but back then these issues were largely invisible within the public discourse. Although there were many NGOs, activists, researchers and even some politicians working to change the situation, back then halting climate change and the extinction of species was a niche concern. Still, I was naively optimistic that more knowledge would lead to more action.

Fast forward to 2024. Today, millions more people are aware of the dangers of both climate change and biodiversity loss. The message from scientists is loud and clear. For example, a recent meta-analysis of papers on climate change and extinctions found that “extinctions will accelerate rapidly if global temperatures exceed 1.5°C. The highest-emission scenario would threaten approximately one-third of species, globally.” The most recent UN Emissions Gap report emphasizes that we are course for a temperature increase of 2.6-3.1°C over the course of this century. Yikes.

The Dismissives

Is the message really so loud and clear? Unfortunately, it is not. Efforts to deny, trivialize, minimize or ignore the dangers of climate change and biodiversity loss remain remarkably strong, and disinformation campaigns seem to be growing. In Climate and Society, Robin Leichenko and I associate such efforts with the “dismissive discourse.” This discourse influences political add cultural debates about environmental policies and actions and it affects whether and how climate change and biodiversity loss are portrayed in the media and in many educational settings.

The dismissive discourse is not driven by a lack of knowledge, but by ideology and vested interests. A recent article in Desmog describes the growth of a sprawling coalition of free-market think tanks worldwide. This network’s disinformation efforts in the late 1990s and early 2000s contributed to decades of delay in climate change policies and actions.

So now we have to make up for years of climate inaction and face the consequences of our responses, or lack of response. Yet instead of electing wise leaders with integrity and a clear vision for what an equitable and sustainable world can look like and how we can achieve it, many countries are electing demagogues who seem to delight in their efforts to accelerate global warming and the sixth mass extinction on planet Earth. We do not seem to be aware that we are entangled with the fate of the dodo.

Dodos

The dodo was a flightless bird native to Mauritius that went extinct over a period of less than a century. My grad school notes tell me that the dodo is the archetype of extinction. In fact, this bird was “designed for extinction.” But the dodo’s extinction was not due exclusively to a design fault. It can be attributed to overharvesting, deforestation, and the introduction of invasive species. Not by dodos, but by humans.

Back when the dodo went extinct (the last sighting was in 1662), the concept of “extinction” did not yet exist. There was no collective awareness that animals could disappear and be gone forever. A course called “Extinction of Species” would have made no sense to people before the 1800s.

This makes me wonder what concepts and ideas we may be collectively unaware of today. Which courses might future graduate students be taking to understand the way we saw the world in the 2020s, and what we were missing?

A new course

If I were asked to design a new course for these future students, I’d call it “The Entanglement of Species.” This course would focus on the inherent oneness of people and nature, and on the relationships between mind, meaning, and matter. It would provide an in-depth education on how society became aware of entanglement — both as a concept and as a motivation to transform relationships with nature and each other. It would focus on how an awareness of entanglement helped us to respond rapidly to both climate change and biodiversity loss.

Emulating my extinction professor, I would start the course by saying that “academic concern about the entanglement of species” is a recent phenomenon. The lectures would begin with a description of revolutionary aspects of quantum physics, groundbreaking experiments on quantum entanglement, fascinating findings from quantum biology, and cutting-edge research in quantum social science. The course would include lectures on Indigenous philosophies and wisdom traditions, consciousness, the psychology of intraconnections, intuitive interspecies communication, entanglement in music art, and literature; the role of ceremony and experiential practices, the politics of entanglement, the relationship between individual and collective change, healing collective trauma, social fractals, and quantum social change.

My mind is spinning with ideas, and I’d love to start designing, organizing, and co-teaching such a course tomorrow. However, we are still going through the background messages of the IPBES transformative change assessment. First things first.

Back to the present

Now it’s back to the plenary approval session — I am exhausted but enthusiastic, and looking forward to celebrating the report’s final approval with the author team.

It’s at times like this I remember the words of my “Extinction of Species” professor. On the last day of class, back in 1988, he told us that “you are alive at the most important time in human history. You have the opportunity to make an enormous positive impact on the world.” As we engage with governments on the final edits of the assessment, I remind myself that small changes can make a big difference.

Biological diversity is messy. It walks, it crawls, it swims, it swoops, it buzzes. But extinction is silent, and it has no voice other than our own.

— Paul Hawken

Who was that professor? I believe we need to name these mentors who were ahead of their time so we can honor them. One of mine was Theo Coburn who wrote, Our Stolen Future. The ten-year anniversary of her death is today.

If you are in Namibia, I recommend you consult with Mama Visolela Namises. She can talk to you straight about entanglement. I hope there are indigenous people at your gathering. Mama Visolela, sometimes called the Rosa Luxemburg of Namibia, walks her talk and has since she was a teenager. She is a force of nature.

Thanks for all your good effort, Karen. When you have some down time, allow me to recommend a book that is not only directly on point here, but at the same time a great escape (can a book be both? YES!). Richard Powers' new book "Playground" ~ if, like me, you are a YUGE Sylvia Earle fan, you will flat out LOVE this book. Reading it's early pages on the first ocean expeditions with SCUBA capability, it is so amazing to think all this has happened in my/our lifetime. Which leads me to think that when we finally get around to putting all our efforts into regenerating Earth, in the same way we decided to go to the moon less than a lifetime after the Wright Bros., imagine how much GOOD we could do in a similarly short time span! Yes, entangled species. Enlisting Gaia as our ally instead of seeing Her as our foe, rival, or lab rat. Working with keystone species AS a keystone species. Your work is crucial, Karen, as is all those working on IPBES. Nature is the Answer to all of our questions and dilemmas.